What Role Does a Living Trust Play in an Estate Plan

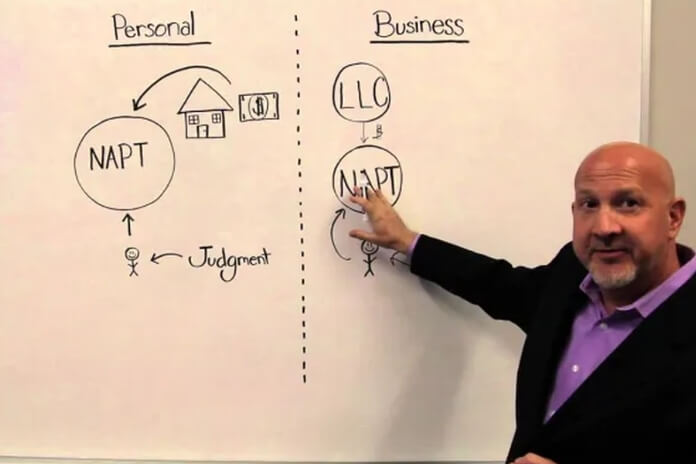

A Living Trust (a/k/a: Family Living Trust, Family Revocable Living Trust, Revocable Living Trust, Revocable Trust), is primarily designed to accomplish two things:

(1) To prevent your family and your estate from having to go through the Probate Court process in order to have your assets distributed to your family (or according to your desires) following your death; and

(2) To address the distribution of property issues following your death (i.e., spelling out “who gets what” when you die).

How Does the Living Trust Avoid Probate?

The Living Trust prevents your estate from having to go through the probate process primarily because the Living Trust is created during your lifetime and it becomes the owner of all of your property, both real and personal. Even though the Living Trust will own all of your property, you still control everything until the day you die or become incapacitated. Because the Living Trust owns everything when you die, you own nothing.

Your personal estate consists of your property that you own. If the Living Trust owns all of your assets when you die, you own nothing and therefore have no personal estate that needs to go through the probate process.

What is Probate? Put simply, the Probate Process is really just the legal process of accounting for and distributing the property of the deceased person to the deceased person’s heirs. Without the probate process, the heirs cannot receive proper legal title to any of the assets of the deceased person. The probate proceeding is a statutory process that is designed to enable all interested parties to come and make their claims against the estate (creditors and potential heirs). The probate process also enables validation of the Will (where there is a Will). The legal process then determines what the valid claims against the estate are (debts & liabilities) and, ultimately, how the net proceeds of the estate shall be distributed. [Where there is a Last Will and Testament, the provisions of the Will spell out who gets what – where there is no Will, the deceased person is said to have died “Intestate” and the Intestate laws of the state where the person dies spells out who gets what according to the law and no one has any say in the matter (your wishes and desires are irrelevant in the case of an Intestate estate)].

The Living Trust that is properly “funded” (meaning that it owns all of your property) will avoid the probate process all together. This is because the Living Trust owns all of the assets and there is no estate (property) that needs to probated.

How Does the Living Trust Work?

When you create the Living Trust (which is traditionally called “settling” the trust), you do several things in the Trust document:

(1) You designate the Trustee (usually you – or in the case of a married couple, usually both the husband and the wife are the Trustees);

(2) You designate one or more “successor trustees”. The Successor Trustee is the person that steps into the role of Trustee upon your death, your incapacitation or your resignation.

(3) You designate the lifetime beneficiary(ies). If you are single, you are usually the sole beneficiary of your Trust during your lifetime. If you are married and you create a joint trust with your spouse, both the husband and the wife are usually the designated lifetime beneficiaries.

(4) You specify the Plan of Distribution of the assets or proceeds of the Trust following your death (i.e., you specify “who gets what”). This is called designating the death “beneficiaries”. In this respect, the Living Trust serves as what is often referred to as a “Will substitute”.

During your lifetime, you (or you and your spouse) ordinarily are the Trustee and you have custody and control of all of the assets of the Trust. You are also the beneficiary of the Trust, so everything in the Trust is for your benefit during your lifetime. With a Living Trust, you have unfettered control over what you do with the assets and proceeds of the Trust for so long as you are the Trustee.

Upon your death, the designated Successor Trustee becomes the acting Trustee of the Trust. The Successor Trustee is bound by the terms of the Trust and the Trust has spelled out how the Trust will be administered and ultimately distributed. It is ordinarily specified that, upon your death, the Successor Trustee is to liquidate the Trust and distribute the assets, or the net proceeds, of the Trust to the individuals that you have designated (for example: “distribute all to my children in equal shares”). The Successor Trustee carries out the distributions as specified and then closes out the Trust after the final distribution is made to your beneficiaries. THIS WHOLE PROCESS OCCURS WITHOUT THE NEED OF ANY COURT INVOLVEMENT – which can save your estate a significant amount of money (and time and hassle for your family), because attorneys fees, court costs, appraisers fees, etc. are all either avoided or minimized.

It is as simple as that!

In contrast, a Will is really a ticket to probate court. This is because the Will is not an entity like the Trust. The Will is merely an instrument that spells out your desires as to who gets what when you die and who will be the executor of your probate estate. The Will really only comes to life following your death. The Will must be submitted to the probate court and go through the entire probate process in order for its terms to be carried out. This can cost your estate a significant amount of money (and time and hassle for your family – sometimes several years) and the bottom line is that your family gets less of your estate and it takes them much longer to get it than they ordinarily would with a Living Trust.